Hearing reveals frustration about proposed closing of Providence Hospital

Decision by health agency on next steps expected this week

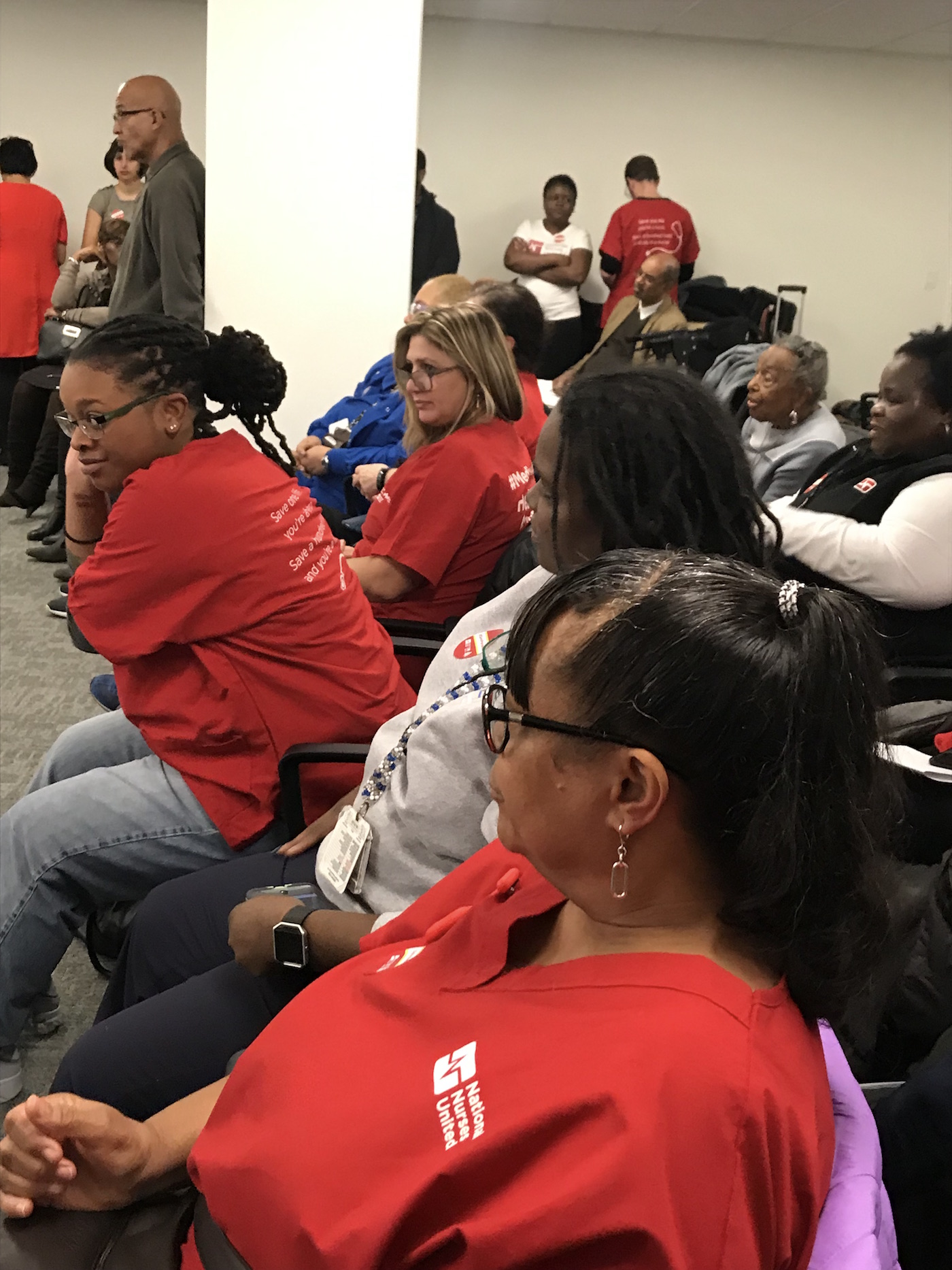

Providence Hospital workers and concerned community members turned out in force at a DC government hearing this month, expressing frustration and disappointment with the planned closure of Providence Hospital in Northeast next month and a perceived lack of transparency regarding the decision.

Ascension Healthcare, a St. Louis-based nonprofit corporation, insists it is not leaving the District but instead is changing its service model. Ascension officials defended their plans from the public criticism at the Nov. 16 hearing convened by the DC State Health Planning and Development Agency (SHPDA) soon after the DC Council passed an emergency bill to delay or block the closure and ensure governmental review of the plans.

SHPDA, which is part of the DC Department of Health but has independent authority, will issue a decision this week “on the path forward for Providence Hospital,” according to Sean Barry, communications director for the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services.

The recent hearing began with a presentation by Patricia Maryland, president and CEO of Ascension Healthcare, who recited the financial losses that Providence has endured since 2012. “Over the last six years Providence has experienced a 48 percent decline in patient volume [and a] $168 million cumulative operating loss, with $111 [million] of that loss coming from the last three years,” she said.

Ascension has attributed the loss in revenue to a decline in the quality of customer service and an antiquated facility on Varnum Street NE in Ward 5’s Michigan Park neighborhood. Providence — which largely serves residents of wards in the eastern half of the District — recently failed an inspection that was required by the DC Health Department, which had ordered that certain deficiencies be resolved. Maryland stressed, however, that Ascension — the world’s largest Catholic health system — remains committed to the District and to serving DC residents.

“We are not leaving the District,” she said. “We need to look at transformative models that are focused on improving a person’s health rather than solely caring for them only when they are sick.”

Keith Vander Kolk, Ascension health system president and CEO of its Baltimore/Washington Ministry Market, reinforced Maryland’s testimony about the losses Ascension continues to absorb while trying to keep Providence Hospital afloat. He said that most residents with private insurance decide to go elsewhere.

“Eighty-six percent of our patients are either Medicaid- or Medicare-dependent,” he said. “The residents of the ward or wards that Providence serves have coverage beyond Medicaid and Medicare. Those patients are not choosing to come to Providence.”

The hospital is licensed for 238 beds but currently serves about 50 inpatients.

Amha Selassie and Thomas McQueen from DC’s SHPDA challenged Ascension about the selection of Dec. 14 as the date for closure, the whereabouts of the money previously invested in the hospital, and the health system’s plans going forward.

“In order to serve, we need to expand our payer mix. We need to update our physical plant and facilities in order to be competitive with other hospitals,” said Vander Kolk.

Providence began as a teaching hospital on Capitol Hill during the Civil War in 1861. President Abraham Lincoln signed an Act of Congress to charter Providence Hospital, the longest continuously operating medical center in DC. Over the years the hospital has taken hits including the 2013 collapse of Medicaid provider DC Chartered Health Plan Inc., which left the hospital with more than $60 million in hospital bills. Providence laid off almost 40 workers that year to reduce operating costs.

(Photo by Candace Y.A. Montague)

Although Ascension recently invested in a fully equipped, state-of-the art emergency room for Providence, it hasn’t been enough to redeem the institution’s reputation. The hospital has maintained a ‘D’ average score in safety from Leapfrog Hospital Safety Grade for the last eight grading cycles and currently has a one-star rating with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, a federal agency.

Ascension officials said their new model will focus on the services that the DC government’s own plans describe as lacking in the city. “Based on the District’s community health needs assessment and the DC health system’s plan, three key health needs were identified in the District,” Maryland said. They include coordinating care for chronic health conditions, addressing the needs of the aging population, and providing mental and behavioral health services.

“[We are] transitioning from a hospital-based service to primary, behavioral health and community-based service,” stated Vander Kolk in his remarks at the SHPDA hearing.

Hospital workers at the meeting were there to fight for their jobs and for their patients who are already being shifted to other health care facilities in the city, they said. Some of the employees have worked at Providence for more than two decades. Many of them are also Ward 5 residents. Anita Jordan Duckett, a respiratory therapist, was upset as she noted that the hospital isn’t living up to its purpose.

“I have lived here for 39 years,” she said. “I haven’t received any notice in the mail that the hospital is going to close. And neither [have] my neighbors. And I work there. They have kept this under the cover. They could have improved the infrastructure of the hospital. We can go outside and get hit by a car, have an asthma attack, have a stroke. You need an emergency room. You don’t treat people like this. This is not the mission. You’re supposed to care for people. I heard very little about patient care. We work too hard for this.”

Providence will continue to provide some primary care, including geriatric and outpatient behavioral health services; the skilled nursing unit will also remain in place at Carroll Manor, which is located on the campus. The health clinic for DC police and fire department employees as well as health services for Catholic University students will also continue.

Last month DC Council members unanimously approved an emergency bill in an attempt to slow down or stop the closure. The legislation, written by Ward 7 Council member and Health Committee chair Vincent Gray, doesn’t guarantee the hospital will keep its doors open, but it does give Mayor Muriel Bowser the power to force the hospital to continue operations. The emergency legislation remains in effect through Jan. 30; the council has not yet transmitted a longer-term version it approved on Nov. 15.

Providence began informing employees about the decision to close in a series of town hall meetings in June. Patients were informed through hallway signs and letters from their physicians. The community, however, claims that it did not get timely or adequate notice of the closure plans, with no opportunity for input prior to the official public announcement in July that even then offered few details.

There are two other emergency rooms within a five-mile radius of Providence: Howard University Hospital in Ward 1 and MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Ward 5. While Howard is working on expanding its obstetrics ward to absorb the former patients from Providence and Ward 8’s United Medical Center (both of which stopped offering maternity services last year), the inpatient mental health facility at Washington Hospital Center is already operating at capacity.

Gregory Argyros, CEO of Washington Hospital Center, testified that the hospital already operates at 85 percent capacity. He stated that after Providence closed its obstetrics ward, Washington Hospital Center saw an 11 percent increase in demand for services for women. Inpatient psychiatric care has increased almost 19 percent. He testified that patients have been boarded in the emergency room because there were no beds available in the psychiatry unit.

”We are increasingly concerned about the safety of our patients and staff,” he said. “We have had to increase the number of sitters for patients suffering from psychosis or suicidal ideation. We already treat nearly 90,000 patients annually in our emergency department, so it is very difficult to believe that we can absorb much more. We cannot expand our capacity.”

Providence physicians spoke out about the potential impact the hospital’s closure would have on the community. Internist Steven Seabron testified that Providence could still regain the public’s trust and become viable once again if Ascension were to make the appropriate investments in the facility.

“The community that the hospital has served for the last 50 years will be impacted,” he said. “I am not in favor of shutting the hospital down. The hospital is there and it’s functional. It’s worth saving. I hear that people are bypassing Providence to go to other places. I feel like that has to do with the lack of commitment that has been made to Providence Hospital to make it a place where people want to come.”

This post has been updated to remove an erroneous reference to the DC State Health Planning and Development Agency having authority to bypass the requirement for a certificate of need.

Washington Adventist Hospital Emergency department is also less than 5 miles away