Maya Martin Cadogan: Real school choice starts with parent voice

Why is your children’s education so tied to where you can afford to live?

Because the river of inequity in our city runs deep, especially when it comes to our schools.

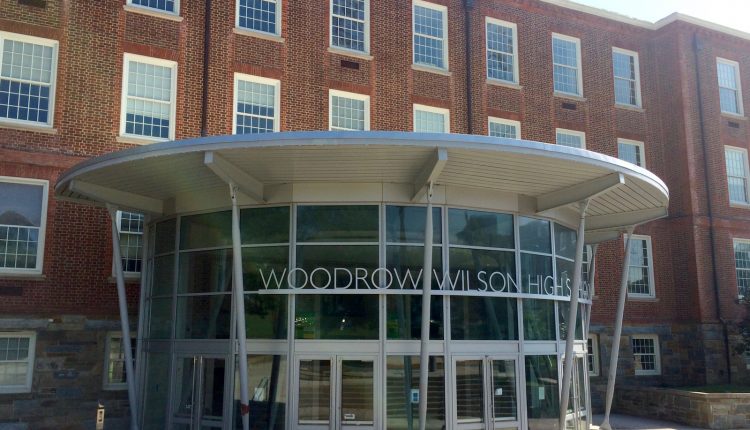

As DC parents finalize their school preferences before upcoming lottery deadlines, it’s worth resurfacing a recent study by the D.C. Policy Center. It found only one area of the District — the far northwest corner — where a large proportion of families (79 percent) choose to attend their “in-boundary” DC public school, because it feeds into the much-desired Wilson High School. Elsewhere in the city, we see a great deal of mobility from one school to another, with only 26 percent of families choosing their neighborhood school. Instead, most make a mish-mash of choices, playing the lottery or moving about, all in hopes of winning a “golden ticket” to a school that will meet their children’s needs.

It’s even more painful when you think about what that means east of the Anacostia River. The recent release of the city’s School Transparency and Reporting (STAR) ratings showed that while more than 40 percent of the District’s students live in wards 7 and 8, there is not a single five-star school in either ward — and few four-star schools. There are bright spots: Ketcham Elementary School, led by Maisha Riddlesprigger, and Center City Public Charter Schools’ Congress Heights Campus, led by Niya White, are examples of schools in Ward 8 that are filled with committed educators who authentically engage and partner with their families and communities, and whose amazing students are showing exceptional academic growth in the process. But we still have much work to do when most of DC’s one-star schools are located east of the river.

When we talk about “school choice,” we have to be clear about whether those are true choices or just options. If you’re choosing among a school in a neighborhood you can’t afford to live in, a school where students aren’t growing academically, or putting your child on a one-hour Metro ride every morning to a school far across the city if they can get the school they want in the lottery — well, those aren’t very good “choices,” are they? Parents are making choices, but we haven’t created the education system of great choices that every child deserves.

How do we build a system of great schools for every child?

To live up to the promise of great schools for all kids, families have to be at the center of our collective vision for the education of their children.

Last week, for the second year in a row, our families at Parents Amplifying Voices in Education (PAVE) celebrated DC Parent Voice and Choice Week — because we know that when parents are given information and tools and raise their voices, good things happen in education. In the two years since we founded PAVE, we have seen it over and over:

- A group of Ward 8 and military parents formed the Ward 8 Parent Operator Selection Team (POST), invited school operators to make their case, and chose LEARN Charter Network to open a new school for military and neighborhood students on Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling.

- After choosing “Great Schools in Every Ward” and “One Citywide School Report Card” as top issues for last school year, parent leaders helped get feedback from more than 4,000 families across the city about the information they wanted to see and how it should be presented. The city issued its new report cards in December, incorporating much of the input from parents.

- Parent leaders identified after-school and summer program funding as a critical priority to support the safety and social-emotional development of our kids, and they advocated with their elected officials, took to social media, and successfully pushed for a $10 million increase after years of stagnation and, more recently, decline.

Last week, more than 100 parent leaders participated in separate meetings with Deputy Mayor for Education Paul Kihn, DC Council Chairman Phil Mendelson and 10 other council members to share their vision for the city’s schools. Our parents had identified two top priorities this year and wrote their own statement of beliefs to address them: better mental health supports and trauma-informed training for all schools, and transparent citywide funding. Parents want to make sure that each of our schools — agnostic of sector, but never agnostic of kids — gets what it needs to do this critical work. Our parents closed out their week of advocacy with a celebration, where they heard from Hanseul Kang, DC’s state superintendent of education, and Jessica Sutter, the newly elected Ward 6 representative on the State Board of Education.

What do we need to do to fix the system?

Only by connecting our schools, teachers, leaders, children, families and communities — and our issues — can we accelerate progress toward equity.

All of these issues are interconnected. Look at the issues that PAVE parent leaders have advocated for to date: If you don’t fund schools adequately, provide resources for children’s social-emotional needs, give kids safe and high-quality after-school experiences to extend their learning, and provide parents with the information they need to know about how our kids are doing and how to support them, how can you expect to have a system of great choices?

PAVE’s parent leaders raise their voices because they know that educating a child takes a village and they are passionate advocates for equity and justice. We’ve seen that when parents lead — and their voices are respected — they expand the conversation and create collaborative solutions to the complex problems our schools and education system face. And parents want everyone to be at the table together, so that we can all figure out what we need to do for our kids.

Because, in the end, true choice can only come with true voice.

Maya Martin Cadogan is founder and executive director of Parents Amplifying Voices for Education (PAVE), a nonprofit focused on creating a DC public education system made with families. Maya is a fifth-generation Washingtonian whose great-great grandfather, George Martin, is on the cover of Black Georgetown Remembered, a book about a once-vibrant 200-year-old community that was swept away in one of the first rounds of gentrification in the city.

About commentaries

The DC Line welcomes commentaries representing various viewpoints on local issues of concern, but the opinions expressed do not represent those of The DC Line. Submissions of up to 850 words may be sent to editor Chris Kain at chriskain@thedcline.org.

Comments are closed.