Lowell School to co-host climate change institute that dovetails with humanities curriculum

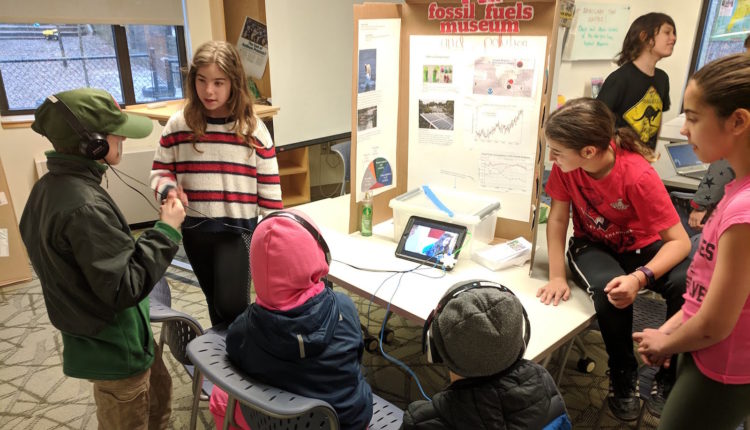

Two years after introducing a new curriculum that uses the humanities to teach sixth-graders about climate change, DC’s Lowell School is looking to help others replicate the program.

“I was looking for a topic in social studies that would really help middle schoolers be motivated to learn complex economics, complex geography, complex physics,” said Natalie Stapert, humanities coordinator at the Lowell School, a private pre-kindergarten-through-eighth-grade institution that has long used its Kalmia Road NW campus adjacent to Rock Creek Park as an outdoor classroom for hands-on environmental lessons.

Climate Generation, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit committed to finding equitable solutions to climate change, helped Stapert come up with the curriculum.

Now, the group is teaming up with the school and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate Program Office to host a three-day summer institute on climate change education. Climate Generation’s 14th annual Summer Institute for Climate Change Education, scheduled for Aug. 5 through 7 at the Lowell School, will promote the inclusion of climate change education in humanities programs.

Climate Generation offers a variety of resources for schools to develop a curriculum that focuses on climate change, but the humanities component is one of its newest offerings. The group’s website explains that the subject is frequently tied into instruction in science, technology, engineering and math — disciplines often lumped together as STEM — but has “political, social, and economic dimensions” that provide a fuller understanding of one of society’s most pressing issues.

At the Lowell School, the innovative curriculum allows students to participate in readings and discussions that help them view climate change through a civics and economics lens, Stapert said.

Stapert spearheaded the program’s fall 2017 launch after she realized that climate change was an issue young people are particularly concerned about.

“This is an area in the curriculum that can be really empowering for students,” said Carolyn Law, the school’s director of communications. “They’re learning how to solve the problems that climate change has caused.”

The curriculum has been well-received by the 37 sixth-graders enrolled at Lowell, according to Kavan Yee, director of the middle school. “There is a genuine interest and excitement to a topic that they can easily connect to,” he said.

One of the books students read for their language arts class is A Long Walk to Water, Stapert said. Linda Sue Park’s 2010 novel, based on a true story, features a young Sudanese girl who travels two hours to retrieve water for her home.

A 2016 report by the National Center for Science Education found that about 75 percent of public middle school science teachers in the U.S. devote instructional time to climate change.

“Almost all public school students are likely to receive at least some education about recent global warming,” the report said.

However, a National Public Radio poll conducted in March found that only 42 percent of all U.S. teachers provide instruction about climate change, while more than 80 percent of parents want their children to be taught the subject in school.

Worldwide, climate change is viewed as the top global threat, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center. The survey found that 59 percent of Americans view climate change as a serious threat.

The science department at Lowell now incorporates more “environmental consciousness” into its course material, Yee said. But coming up with ways to mitigate climate change, he said, requires viewing the issue through various perspectives in addition to a scientific lens.

The evolving humanities curriculum at Lowell has inspired students to be more politically active in their pursuit of solutions to combat climate change. In February, four Lowell students attended a hearing on climate change at the U.S. House of Representatives.

Stapert said the curriculum’s implementation has prompted teachers to become more passionate about the issue as well.

Jenna Totz, the climate change education manager at Climate Generation, said that the organization helps schools develop their curricula by suggesting books, lessons and articles that can help bring the subject to life for students.

During a spring summit in 2017, staff from Climate Generation visited Lowell to conduct activities with teachers and other staff to help prepare them for the curriculum, Totz said.

This year on Earth Day, teachers and administrators at Lowell led special classes related to climate change and other environmental issues, Yee said. Rather than going to their regular classes, students selected from a slate of workshops, including one taught by Yee on how to make a biochar stove. Scientists say that widespread use of biochar — which is charcoal produced from plant matter and added to the soil — could help reduce climate change by removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Stapert said that the school has “work to do” when it comes to energy efficiency. Although she didn’t offer specifics, she said she expects Lowell to identify areas for improvement. Yee said there are plans for an annual energy audit overseen by the school’s science department.

When it comes to the humanities curriculum, Stapert believes students are appreciative of what they’ve learned so far.

“Kids have expressed a real desire to learn more,” she said. “They see [climate change] as something that they really do need to understand in order to move forward as mature young people.”

This post has been updated to correct Jenna Totz’s title.

Comments are closed.