Decades of setbacks stall the development of a landfill-turned-park in Ward 7

A short walk from the Minnesota Avenue Metro station in Ward 7 is a spot on the eastern bank of the Anacostia River called Kenilworth Park. Despite the name, a large section of the park currently has about as much in common with a vacant lot as it does with most parkland in the District.

The area — administered by the National Park Service (NPS) as part of National Capital Parks-East, a collection of NPS lands situated east of the U.S. Capitol in DC and Maryland — is frequently strewn with garbage. Abandoned athletic equipment sits unused as mud-caked relics of an attempt years ago to turn the area into a viable recreation space despite approximately 4 million tons of waste lying beneath it.

The National Park Service webpage for Kenilworth Park & Aquatic Gardens — which, like the nearby playgrounds, are currently closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic — neglects to mention the landfill, focusing almost exclusively on the gardens and wetlands that make up the northern portion of the park’s roughly 700 acres.

“In an age old dance wind, water, and land combine here,” the page says. “The park reflects the policies that affect rivers and wetlands. Come, join the dance.” An archived version of the page from 2006 is somewhat different: “Mankind has loved, used, and changed the land here.”

With a renewed planning process said to be in the offing, there are those who still want to see the space become an outdoor recreation hub for the Kenilworth Parkside neighborhood and other communities east of the river. Erin Garnaas-Holmes, ambassador to the Anacostia Watershed Urban Waters Partnership with the Clean Water Fund, hopes the park could soon be used for sports fields, urban farms or children’s playgrounds, among other things.

“There are some groups that advocate more for essentially habitat- and wildlife-based restoration, and there are others that are really interested in athletic fields,” Garnaas-Holmes said in an interview with The DC Line. “So there might be some back and forth when the conversation really opens up about how much space is given to each of these. But I think there’s probably space where everybody can have a little bit of everything.”

Open burning

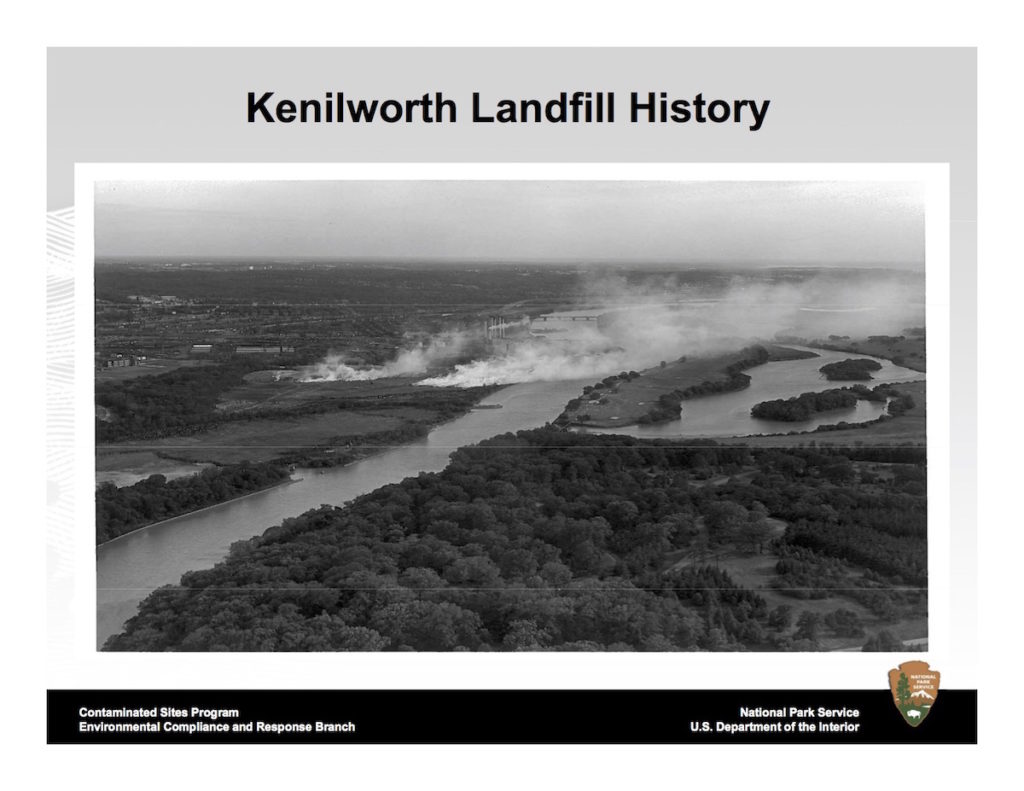

Much of the section of National Capital Parks-East known as Anacostia Park was created thanks to dredging of the river performed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. This section includes Kenilworth Park.

The land administered today by National Capital Parks-East was handed over to the National Park Service in 1933. Less than 10 years later, the U.S. Department of War gave the District of Columbia (whose government was still a federal agency overseen by appointed commissioners) the go-ahead to burn garbage at a location known as Kenilworth Park, and to use roughly 20 acres of the area for a landfill. DC was later given permission to burn in a second area in the park. A permit issued to the District, allowing for the deposit of incinerator waste in an area near the landfill, specified that “all disturbed areas shall be restored” and that “all reasonable precautions shall be exercised to protect park property.”

“[T]he landfill extended directly into the river without any barrier, and landfill wastes mixed with soil entered the water,” according to a health consultation conducted in 2006 by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (In contrast, a geophysical study prepared the same year found the closest that the landfill waste came to any body of water was 30 feet away.)

Smoke from the burning garbage wafted into nearby residential neighborhoods, and according to The Washington Post, locals laid down in front of bulldozers to protest the trash inferno. The burning produced air pollution comparable to the output of 1.5 million cars according to a 1966 DC Health Department report. An internal NPS memo from the mid-1960s — quoted in a 2004 document obtained by The DC Line — complained that “the volume of trash carried daily to the Kenilworth dump … is tremendous and is increasing” and asked “what can we do to stop it?”

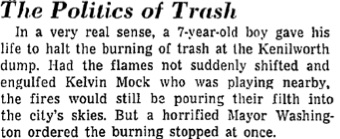

Open burning was finally halted in 1968 after 7-year-old Kelvin Mock died at Kenilworth Park. When winds shifted, the flames from the burning garbage unexpectedly surrounded Kelvin, who was playing nearby with friends.

Although Mayor Walter E. Washington, a presidential appointee at the helm of the District’s pre-Home Rule government, acted quickly to stop open burning after Kelvin’s death, the area continued to be filled with raw municipal waste. That lasted until the early ’70s when three feet of sediment from the Anacostia (followed by a slurry of surface soil and what may have been sewage sludge) were used to “cap” the landfill. The soil cap was not considered to be impermeable, meaning liquids and gas from the landfill could still potentially pass through.

Soon after, Russell E. Dickenson, then the director of National Capital Parks, said that the development of Kenilworth into a viable park would cost between $1 million and $1.25 million. Still, Dickenson worried about whether trees could be successfully planted on the site.

“Below the three or four feet of topsoil, there’s just deteriorating trash,” Dickenson told The Washington Post in 1972. “Nobody knows how the trees will react when their roots reach that level.”

Unauthorized dumping

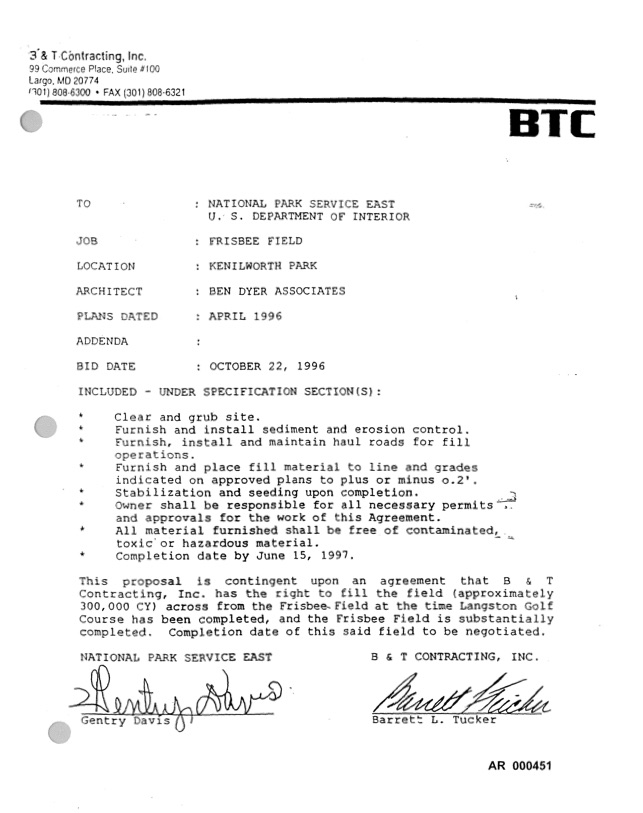

In the years after it was capped, the public grew accustomed to using Kenilworth Park as a park. This is in part why neighbors took notice when trucks carrying rubbish started showing up again in 1997. Over the course of two years, somewhere between 2 and 20 feet of construction waste was dumped at Kenilworth Park.

The dumping of trash took place in spite of an agreement spelling out that any material used for fill at the park would be “free of contaminated, toxic or hazardous material.”

The stipulation can be found in a document signed by Gentry Davis of the National Park Service and Barrett Tucker of B&T Contracting Inc., a trucking company. Another Maryland-based company, Driggs Corp., also dumped at the park during this time, although its agreement with NPS did not explicitly forbid the dumping of hazardous materials, according to The Washington Post.

Unlike in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, dumping in the ’90s occurred without the blessing of the District government, which had by that time achieved Home Rule. According to a letter sent from the DC Department of Health to National Capital Parks-East on Oct. 10, 1998, dumping activities violated the District’s Soil Erosion and Sedimentation Control Act and the Water Pollution Control Act. The letter — obtained by The DC Line in a document request — warned that failure to bring its operations into compliance with DC law would lead to a referral to the Criminal Division of DC’s Office of the Corporation Counsel; the letter also ordered NCP-East to “cease all grading and landfilling operations.”

Davis, National Parks-East superintendent at the time, claimed that the dumping was intended to add another level of fill to the park so that athletic fields could be built on an elevated surface.

Locals were told the dumping was related to “a cosmetic rearrangement of the athletic fields,” despite the fact that the waste from Driggs Corp. contained solid garbage like nails, pipes and steel reinforcement bars.

The junk came from Andrews Air Force Base, National Airport, Pentagon Heating and Refrigeration and a Rite Aid on Georgia Avenue, among other sources. Meanwhile, the nature of the material dumped by B&T Contacting remains largely a mystery. The trucking logs documenting those materials’ origins have gone missing.

Both B&T Contracting, based out of Upper Marlboro, and Driggs Corp., based out of Capitol Heights, are now defunct.

In total, an estimated half-million tons of trash and dirt was hauled into Kenilworth Park in what even NPS later acknowledged as a violation of local and federal environmental laws. According to a 2008 community involvement plan released by National Capital Parks-East, NPS suspected that asbestos and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were dumped in the park during this period.

After dumping was halted, National Capital Parks-East removed most of the debris. An NPS official quoted in a 2000 Washington Post story on the illegal dumping estimated that the park would be usable again by 2001.

Several years before the unauthorized dumping incident, Davis had been quoted in the Post lamenting problems caused by garbage that found its way into the Anacostia.

“Trash is one of the biggest headaches we have on the river,” Davis said. “We spend more money on cleanup than anything.” In February of 1999, Davis was promoted. He became a deputy regional director for the National Capital Region.

The finer points of CERCLA and an unexploded bomb

In the aftermath of the illegal dumping, the National Park Service began a series of environmental investigations at Kenilworth Park.

Beginning in 1998, a preliminary assessment of the site was conducted as part of what was characterized as a Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) cleanup project. CERCLA is a law passed in 1980 that created a fund drawn from taxes on petroleum and chemical companies. This “Superfund” is used to pay for cleanups and remediations of hazardous waste sites cataloged on the “National Priorities List.”

There are currently 1,335 sites across the country on the National Priorities List. Kenilworth Park is not one of them and therefore does not receive Superfund support. NPS frequently namechecks CERCLA (including in a PowerPoint showed at community meeting held in October 2018), but whether the Kenilworth cleanup can be considered a CERCLA project is debatable. Asked in a 2012 interview with WAMU whether Kenilworth Park was a Superfund project, an NPS official said that different people have different definitions of what constitutes a CERCLA or Superfund project, and that Kenilworth Park was being dealt with using “CERCLA response authority.”

According to NPS, when the preliminary assessment and site investigation were completed in 2002, they concluded that Kenilworth Park required additional study to determine whether it was safe. Strictly adhering to the CERCLA protocols they outlined at the 2018 community meeting, the next step would have been to complete a remedial investigation.

However, in 2006, the DC Sports & Entertainment Commission — then in the midst of planning for Nationals Park and related community amenities — was given the green light from NPS to hire a construction contractor and move forward with a $4.5 million project that would have seen Kenilworth Park outfitted with new baseball diamonds, tennis courts, a track and other recreation facilities within six months.

On Sept. 19 of that year, the Fort Myer Construction Corp. abruptly halted its work on the project. According to a company memo to the Sports & Entertainment Commission obtained by The DC Line in a document request, a Fort Myer employee had unearthed an unexploded munitions shell the size of a thermos. Fort Myer contacted the DC police, and ultimately the Army Corps of Engineers was summoned to dispose of the bomb.

(A Freedom of Information Act request filed with the DC Office of Contracting and Procurement seeking a copy of the DC Sports & Entertainment Commission’s Kenilworth Park contract came up empty. The commission, now known as Events DC, declined to comment on the incident, and a representative of Fort Myer Construction Corp. said no one at the company remembered the incident.)

Roughly a year after work on the sports facilities began and ended, the remedial investigation finally was completed.

The contaminants

During the remedial investigations at Kenilworth Park, the smells of diesel and petroleum were reported after workers bored into the landfill, according to a supplemental groundwater study prepared in 2016. Depressions on the surface of the landfill may have resulted from the collapse of decomposing matter below, the report said.

The investigation found lead, arsenic, pesticides (specifically dieldrin), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and PCBs present on site. The substances were found in surface soil, subsurface soil and the buried waste.

Arsenic is a naturally occurring carcinogen that can wind up in soil through a variety of channels, including pesticide usage, mining waste and volcanic eruptions. The use of pesticide dieldrin (sometimes known by trade names like Red Shield, Alvit, Deildrix, Quintox and Octalox) was discontinued by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1970, but it was approved for use on termites two years later. It was banned again in 1987 when the manufacturer agreed to terminate its registration. Most dieldrin exposure occurs via contaminated meat. It has not been determined whether dieldrin is carcinogenic, but it seems to have an adverse effect on the nervous system.

PAHs are generally released by burning, sometimes of fuels like coal or gasoline, but also by the burning of trash. PAHs can be breathed, ingested or absorbed through the skin and they can be carcinogenic. PCBs are endocrine disruptors, meaning exposure can influence human hormones. Before being banned in the mid-1970s, PCBs could be found in consumer and electrical products, including capacitors, transformers, lubricators and coolants. Extended exposure to PCBs, which can be ingested, breathed or absorbed through the skin, can cause developmental defects, miscarriage and neurobehavioral issues in children.

NPS determined that exposure to these substances posed a risk to those who visited the park, and in 2013 they proposed a plan to make the park safe again: a 2-foot cap of impermeable soil placed on top of the landfill. This plan, however, has been shelved due to concerns related to contaminants in the groundwater beneath the park.

A 2019 addendum to the remedial investigation found that contaminants in the groundwater were not present at dangerous levels, but concerns have long persisted about the groundwater beneath Kenilworth Park migrating into adjacent bodies of water like Watts Branch (a tributary of the Anacostia) or Kenilworth Marsh.

Arash Massoudieh, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Catholic University of America, said in an interview with The DC Line that it is difficult to account for all the uncertainties associated with safely developing Kenilworth Park. Though he acknowledged that an impermeable soil cap might protect people using the park, he said it does nothing to prevent potential contamination of the river — a problem that might require action regardless of any new recreational uses.

“I don’t see any way that adding a layer of soil is going to hurt. It probably will help, at least from the air quality perspective,” Massoudieh said in an interview with The DC Line. However, he would favor more robust action. “In general, when you have a contaminated site at this scale in a densely populated area, like in DC, and close to a river, it has to be cleaned up,” he said.

It could be a serious cause for concern if a sufficient amount of the sorts of contaminants identified at Kenilworth Park reached the Anacostia.

Colorless and tasteless, arsenic most commonly ends up in the human body via water. According to EPA standards, drinking water should not contain more than 10 parts per billion of arsenic.

In addition, according to a DC Department of Health study quoted in the remedial investigation, there have been advisories issued due to high levels of PCBs detected in fish reeled in from DC waters. Although the DC Department of Energy and Environment (DOEE) strongly encourages catch-and-release fishing, tens of thousands of people eat fish from DC’s rivers.

Silence after October 2018 meeting

In October 2018, NPS held a community meeting for those interested in the state of the park. Garnaas-Holmes was among the attendees.

“There was definitely some disgruntlement,” Garnaas-Holmes said. “Like, ‘We haven’t heard anything from you guys since like 10 years ago when the last thing happened.’”

Both Garnaas-Holmes and Dennis Chesnut, an activist who lives in his boyhood home near Watts Branch, see the historical Kenilworth Park dysfunction as a symptom of a divided District, with low-income people of color east of the river and more affluent areas to the west. As a child in the ’50s and ’60s, Chesnut would pass the Kenilworth landfill to go play in Watts Branch due in part to segregation policies that barred him from public pools.

“I believe now I’ll be able to swim in the river again in my lifetime,” Chesnut said in an interview with The DC Line. “If someone had said that to me 20 years ago, I probably would have said, ‘Well, it might be possible.’ But now I believe it’s going to happen.”

Chesnut was instrumental in the grassroots movements to implement the plastic bag fee and the polystyrene ban in DC, among the various initiatives that are helping to clean up the Anacostia River. According to Chesnut, the October meeting was informative, but many community members left with questions.

A presentation shown at the meeting identified the project as a CERCLA cleanup and described CERCLA as being “commonly known as Superfund.” The slideshow placed the NPS at the remedial investigation phase and cited over a half dozen studies conducted between 2013 and 2018. It listed four major contaminants: PAHs and PCBs (in the surface soil), lead (in the subsurface soil) and iron (in the groundwater). Arsenic and dieldrin were not listed.

The presentation also teased a remedial investigation addendum report in November 2018 and a feasibility study addendum in January 2019. Although NPS missed both target dates,, the remedial investigation addendum report was released in June 2019. It reported statistically minor risks from contaminants in surface soil and groundwater. On the other hand, the addendum warned that precautions had to be taken to protect future construction workers at Kenilworth Park from lead in the subsurface soil and, possibly, more unexploded ordnance. According to an NPS spokesperson, next steps will be outlined in a feasibility study addendum this summer.

Massoudieh of Catholic University said remediation on this scale is a significant challenge. He notes there might be another, less expensive option: “natural attenuation.”

“That’s a fancy word for not doing anything other than continuously monitoring the level of contaminants in the soil, storm runoff and air. So basically, just leave it there and then time helps so the pollutants are just stabilized or biodegraded or diluted,” Massoudieh said. “They basically leak into the river or go to the aquifer but at levels that don’t cause the pollutant level in the receiving waters to go beyond water quality thresholds, and hope for the concentration in the site to go below the acceptable levels by passage of time. Modeling studies can potentially inform us about how long this process will take. …

“I think doing some active cleanup is better, but it can be highly costly for a contaminated site of this size,” Massoudieh added.

Given the false starts and setbacks that have plagued the project through the decades, some might be tempted to sit back and wait for natural attenuation to take its course. Chesnut has a more proactive outlook. He remains optimistic that, so long as the community keeps putting pressure on the local and federal governments, Kenilworth Park — as well as the Anacostia River as a whole — will move in a positive direction.

“I’ve been called a blue-sky guy sometimes,” Chesnut said.

In an interview with The DC Line, Siraaj Hasan, acting chair of Advisory Neighborhood Commission 7D, pointed to a lack of consensus on who should bear the bulk of the cost of remediation as an explanation for the recent delays. Still, Hasan plans to help champion the park’s development this budget season.

“We’re going to push our councilman to make that a priority. … We’ve been on the sideline long enough,” Hasan said. “The park was always a bridge between Kenilworth and Mayfair, Paradise, Eastland Gardens. It brought the entire community together.”

Thank you for your well researched article. Kenilworth Park is that last remaining large parcel of relatively undeveloped waterfront on the Anacostia. Curious that no facilities for swimming, wading, boating or any other water dependent activities are planned for this important future waterfront park. Before dumping and landfill began this property was primarily a wetland important to the health of the Anacostia and for flood protection for Watts Branch. As we approach a swimmable Anacostia we must insure that the river will remain so by restoring the important functions lost when these and other wetlands were destroyed by “legal” municipal dumping and burning. 4000 meters or so upriver and 10 or so years ago, the Bladensburg Wetland (ANA11) was recreated at a former dump site. It is now a beautiful attraction along the Anacostia River Trail serves as a model to for what Kenilworth Park could become. A well considered project which includes re-creating and connecting wetlands to the Anacostia can provide new opportunities for water contact activities as well as increase access to recreation. Parks which achieve these outcomes are being created all over the world. The Upper Anacostia is one of our most beautiful and precious natural areas. We cannot afford to miss the unique opportunities afforded by this waterfront as plans move forward to reclaim this land. Thanks to all who have spent their lifetimes bring the Anacostia back to life.