Poor air quality may have more impact on the health of vulnerable communities

By Courtney Curtis, Marymanita Mensah, Johnathan Morales, Daniel Oloju, Shaunavahn Reid, Janae Wilson and Anthony Yang

Global warming is a worldwide problem, but it is felt more acutely in some places than others.

Maranda Ward says her neighbors in Southeast DC suffer disproportionately from poor air quality and scorching summertime temperatures — and, in 2023, from the persistent smog caused by the Canadian wildfires.

“Climate change impacts the world, not just Southeast DC,” says Ward, an assistant professor and director of equity at George Washington University’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences. “But the reason there remains a disproportionate impact on historically disinvested neighborhoods is because of structural inequity.”

An example of that: Urban areas typically have more concrete than they do green spaces.

“Given how climate change has increased temperatures overall, these concrete jungles are especially overheated and exacerbated by emissions from cars and trucks, industry, and poorly circulated housing conditions,” Ward says. “This is why we should care about what is the relationship between urban America and climate change.”

Among DC’s eight wards, asthma is most common in Ward 7, where Ward lives, and Ward 8. These two wards have the lowest median income in DC as well as the highest rates of children living below the poverty line. Kids living in Ward 8 have 20 to 25 times more emergency department visits than children who live in higher-income neighborhoods, according to data collected by Children’s National Health System. Children in Ward 8 are 10 times more likely to be hospitalized for asthma than kids in DC’s more affluent neighborhoods, the study found. People living in wards 7 and 8 also have the highest rates of smoking, diabetes and stroke in the District.

“Despite the rich history and culture of communities east of the Anacostia, these neighborhoods have been historically disinvested and impacted by environmental racism,” Ward says.

Those who have jobs involving manual labor outside are more likely than white-collar workers to be affected by bad air — and people who work in those jobs are more likely to be people of color living in disinvested neighborhoods.

“Minority and low-income communities are always at risk of climate-related maladies just by going about their daily lives,” Ward says. She calls that a form of environmental racism.

“You can track and see places where more people of color are impacted,” she says. “People with less money — who are forced to live near landfills and highways and freeways going through their neighborhoods — are going to have high air and water pollution.”

Public health officials around the country tracked the daily Air Quality Index (AQI) during the 2023 wildfires and recommended that people at higher health risk stay indoors or use N95 masks if they had to go out. (The masks may offer some protection from breathing in harmful particles generated by the smoke from the fires.)

Jono Anzalone, former executive director of the Climate Initiative, a nonprofit focused on finding youth-driven solutions to climate change, called 2023’s summer air quality “another wake-up call for communities on the impacts of climate change.”

Seniors, pregnant women, and people living with respiratory illnesses and cardiovascular disease are at particular risk when the air quality is bad. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also reports that children are more likely to be affected by air pollutants because their airways are small and still developing, and they breathe in more air relative to their body weight than do adults.

There may also be a link between poor air quality and an increased risk of developing mental health issues, including depression, according to a study published last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Anzalone says these sorts of conditions will only intensify as climate change worsens. So, what can be done? It’s a global problem in need of global solutions, but Ward says there are some meaningful things that can be done at the local level.

Community-based organizations, she says, “will need to partner with advocacy and policy groups to change legislation that determines city plans, housing developments, opportunities for recreation and green space, as well as the systems that maintain environmental racism.”

In that regard, she applauds the work done by the 11th Street Bridge Park, a community-based organization in DC, for modeling “what equity looks like in community development” as it works to build an elevated park that will span the Anacostia River.

The 11th Street group sought community input and then authored what Ward calls “an equitable development plan for the mayor’s capital investment in a new bridge park connecting the neighborhoods of Anacostia with Navy Yard in ways that won’t displace Ward 7 and 8 residents.”

The plan calls for cleaning the Anacostia River and securing contractors from the neighborhoods for the buildout, all the while maintaining connections to the Indigenous and Black history of Washington. The park is slated to open in 2027, with a recent federal grant providing the last piece of the project’s $92 million construction budget.

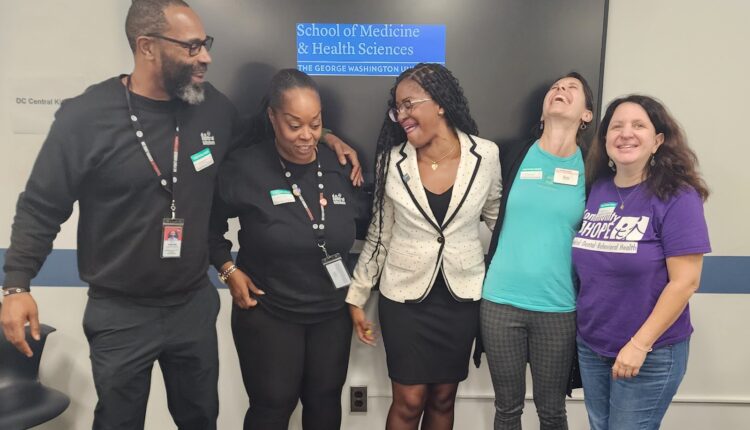

Curtis, a former Youthcast Media Group intern, graduated from DC’s Bard High School Early College with an associate degree. Mensah is a recent graduate of DC’s Banneker Academic High School; Oloju and Yang attended Kenwood High School in Essex, Maryland; and Reid and Wilson are 12th grade students and Morales is a recent graduate at Weaver High School in Hartford, Connecticut. The students participated in a writing boot camp on climate and health. Youthcast Media Group is a nonprofit organization that teaches high school students across the country to report on health and social issues that impact communities of color, and on solutions to these issues.

Comments are closed.