jonetta rose barras: Been there, debated that — health care in DC

It’s all politics, all the time with Mayor Muriel Bowser’s administration. It now appears the Office of the Attorney General has joined forces. Many of us may have thought the city was serious — ready to take it to the mattresses — to prevent the closure of Providence Hospital when it filed its lawsuit against the Northeast facility and its parent company Ascension. DC officials have disabused everyone, myself included, of that idea.

DC Superior Court Judge Geoffrey Alprin issued a preliminary ruling on Thursday in the case, denying a temporary restraining order sought by the city. When I sought a comment on the ruling from Attorney General Karl Racine, his spokesperson Marissa Geller said she was told to refer press calls to the Department of Health. I asked for the name of the person there who was handling inquiries about the administration’s reaction to the judge’s denial of a temporary restraining order sought by the city. Geller told me to speak with Tom Lalley, DOH’s communication director. “The lawsuit was filed on behalf of the mayor,” he said, referring me to mayoral spokesperson Susana Castillo. After I left a phone message for her, she sent me a statement from Jay Melder, chief of staff to the deputy mayor for health and human services.

“While we are disappointed in the Court’s ruling today on the Temporary Restraining Order, the District still has a viable complaint pending in the courts,” Melder said. “We will continue the fight and are pursuing all options, inside and outside the courtroom, to protect patient access to safe and reliable healthcare services at Providence Hospital.”

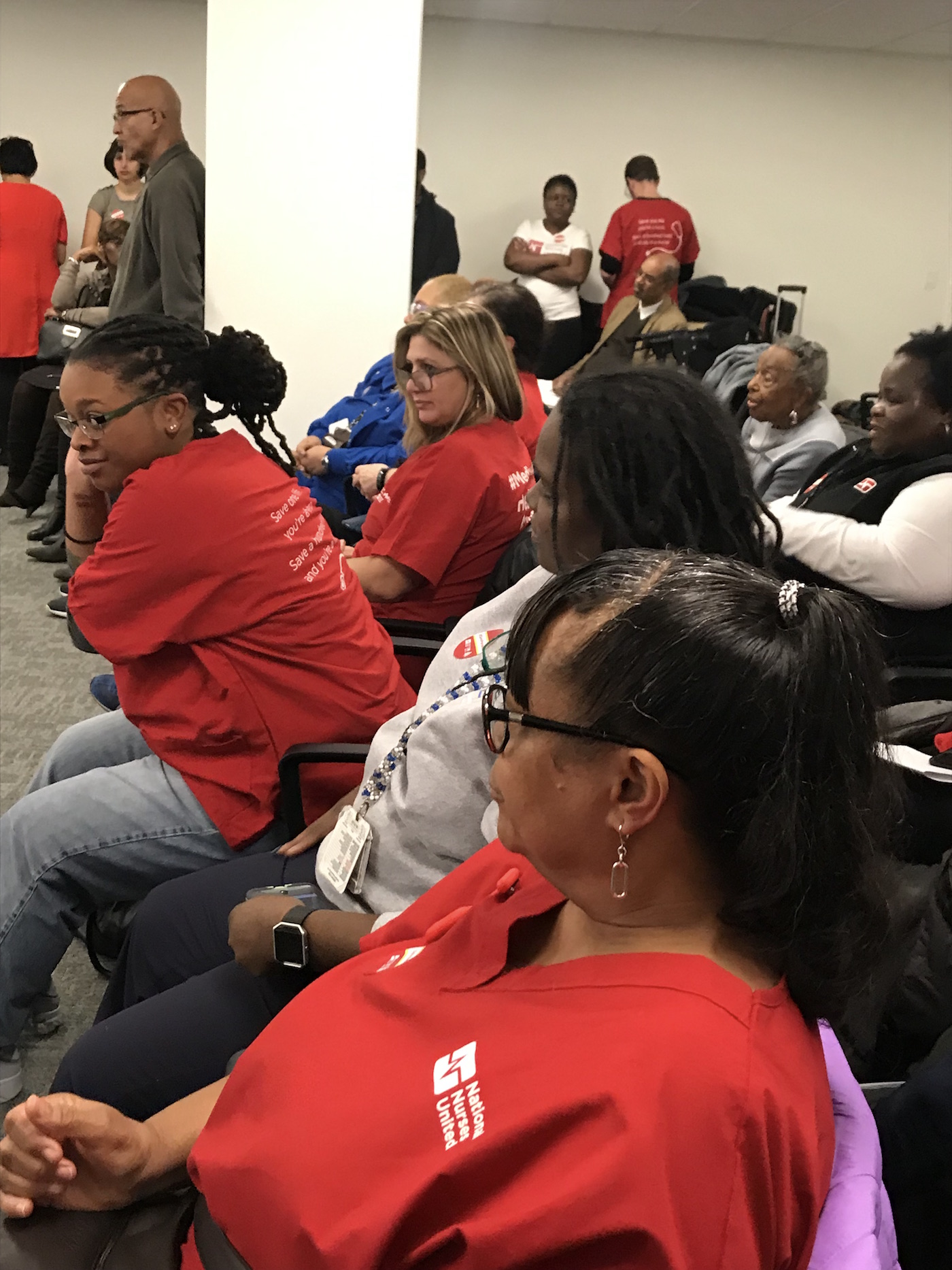

When no one readily claims ownership of a lawsuit, that suggests no one is really committed. The original filing may have been done to appease angry Providence Hospital workers who are about to lose their jobs. Perhaps it was done to satisfy residents who worry that they will be without adequate medical care.

It’s not clear how vigorously the OAG will pursue the case, though further hearings are scheduled early next year. The judge asserted that the city could not block the closure, as the lawsuit had attempted.

Providence — one of the oldest, continuously operating medical facilities in DC — had announced it intended to end all acute-care services by Dec. 14. That decision came as Ascension released a plan for the facility’s future that included what it described as a health village, with an emphasis on medical services that rely on the use of technology.

The DC Council jumped in, passing legislation that clarifies any hospital closure had to be approved by the State Health Planning and Development Agency (SHPDA). After some pressure from the city, Ascension agreed to reduce rather than close its emergency room operations for the time being, putting off the closure until April 2019.

Then, last week, the OAG filed its lawsuit, which accused Ascension of failing to secure approval from SHPDA. As evidence that the hospital had, in fact, begun implementation of a closure plan, Racine cited the declining number of patients and medical units. On Oct. 11, Providence had 87 patients in four different units. By Dec. 7, the number had been reduced to 14 patients in two units. The lawsuit further charged Ascension and Providence with being out of compliance with DOH rules and regulations, which mandate retention of sufficient “staff to operate as a hospital.”

The city has asked the court to stop the defendants from closing Providence Hospital or from altering or eliminating services until SHPDA formally approves a closure plan. Further it has asked that the hospital is stopped from operating the facility in a manner that is “inconsistent with the requirements” set by city law.

In a statement dated Dec. 15, the hospital said it “will continue to maintain primary care services both on campus and at the Perry Clinic, outpatient behavioral health services, the Center for Infectious Disease, Carroll Manor, and services at the Police & Fire Clinic and Catholic University of America Student Health.”

The lawsuit comes as the DC Council grapples with a plan to build a hospital on the campus of St. Elizabeths in Ward 8. That proposed $300 million facility is considered by proponents to be crucial to improving health care outcomes for some of the city’s poorest residents. The council voted to move forward with the plan, although there were several caveats with the legislation, including effecting an affiliation with Howard University to provide opportunities for its medical students to practice at the facility and to ensure hiring preferences for nurses and others now employed at United Medical Center — a city-owned hospital in Ward 8 beset by financial troubles and complaints about inadequate services.

Health care has been a continuing challenge for the District government for more than two decades, including the operation of DC General Hospital before it became a homeless shelter. During the administration of Mayor Anthony A. Williams, the city developed what became known as the DC Healthcare Alliance. Among other things, it guaranteed health care for low-income residents that relied less on hospitals and more on a network of improved clinics whose primary focus was preventive and specialty care for patients.

A 2010 report prepared by the Brookings Institution and The Rockefeller Foundation praised the city’s efforts but acknowledged continued problems. “The District’s health care system is still struggling to improve health outcomes by focusing on chronic diseases, increasing primary care usage and reducing reliance on emergency departments and other hospital-based care,” wrote Jack A. Meyer, Randall R. Bovbjerg, Barbara A. Ormond and Gina M. Lagomarsino — authors of the report. “Moreover, health system redesign does not address the social determinants of health, such as personal behavior, income, education and environmental factors. Improving health outcomes will take not only reforms in health care delivery, but improved education, housing, and job opportunities, as well as changes in diet and exercise and reductions in smoking and substance abuse.”

Tackling these fundamental issues is a big challenge, as the report’s authors noted. “Many of these factors are outside the control of the health care system and require major coordinated efforts across multiple agencies,” they wrote. “There is progress on creating a more integrated health system with less emphasis on hospitals and more on prevention and primary care, but there is a long way to go.” (The DC Healthcare Alliance Program, which is locally funded, continues to provide assistance to District residents who do not have any other health insurance and are ineligible for Medicaid and Medicare.)

Despite improvements over the past decade, the AG’s lawsuit over the pending closure of Providence Hospital and the efforts to build a new facility east of the Anacostia River has reopened an old debate: To hospital or not to hospital — that is the question, once again, for DC officials. Even more fundamental is this: How can we best provide health care services to low-income communities that bring measurable improvements in their health?

This post has been updated based on today’s court decision and the administration’s response.

jonetta rose barras is a DC-based freelance writer and host of The Barras Report television show. She can be reached at thebarrasreport@gmail.com.

Comments are closed.