Alison Collier: Don’t balance the budget on the backs of vulnerable children

Beyond the tragic toll of fatalities, intensive-care intubations and infections that have forced a radical rethink of daily life, the coronavirus has brought a halt to the District’s strong economy and the revenue it generates.

To accommodate this budgetary reversal, Mayor Muriel Bowser has frozen government hiring, salary increases and travel, with exceptions for the city’s pandemic response, public safety, human services and school staffing. The mayor’s budget proposal, postponed to May 18 to be reworked in light of the global pandemic, will have to reflect an estimated revenue loss of $722 million through September and $774 million in fiscal year 2021, necessitating fiscal tightening, according to DC Chief Financial Officer Jeffrey DeWitt.

The District had a record 77 days of reserves at the year’s start, but the lockdown has sharply reduced recently buoyant tax receipts. The shuttered hospitality industry alone provides nearly half the District’s $1.6 billion annual sales tax revenue.

The federal government exacerbated the problem by breaking with previous practice by classifying the District as a territory in its stimulus legislation. That translates to around $700 per capita in federal funds for the District of Columbia, compared to at least $2,000 per person for residents in the smallest states. The District has a larger population than Wyoming or Vermont and sends more in income tax receipts to the federal government than 22 states, yet was categorized as a territory, depriving DC of $725 million in federal assistance it would have received if treated as a state.

Absent millions in federal and local revenue, economies have to be made. But the important question is who should bear the greatest burden.

Much has improved in DC governance since a quarter of a century ago when the federal government imposed a control board to oversee the District government’s parlous finances. But in public education, a judicious mix of increased investment and reform — the 1995 DC School Reform Act, which established public charter schools, and the 2007 Public Education Reform Amendment Act, which instituted mayoral control over DC Public Schools — has achieved hard-earned results that deserve budgetary protection.

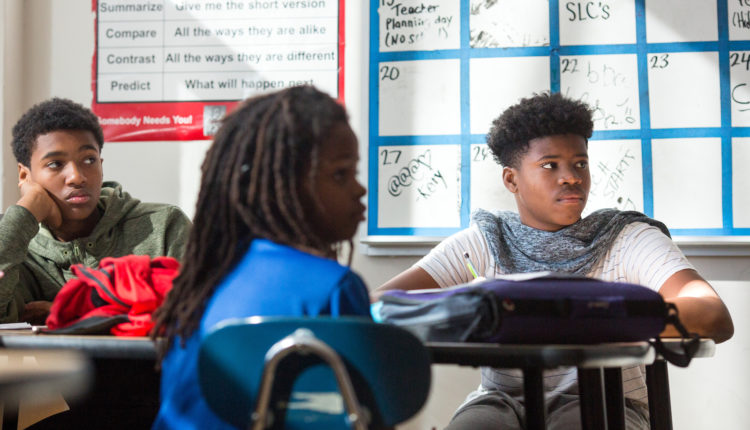

Student performance as measured by standardized test scores and on-time high school graduation rates has improved, and public school enrollment continues to rise year-on-year after decades of decline. In wards 7 and 8, the city’s most underserved, public charter school students are nearly twice as likely to meet or exceed college and career readiness benchmarks as peers in city-run schools. Charters’ unique contribution — providing nearly half of the District’s public school students with a tuition-free education independently of the traditional public school system — has proved a solid investment in the city’s most vulnerable communities.

But despite the progress of recent years, the student achievement gap remains stubbornly high. Overall, 85% of white students meet citywide standards in English language arts and 79% do so in math; among their African-American peers, these numbers are only 28% and 21%, respectively. These gaps follow students into adulthood, all too often casting a shadow that lasts a lifetime.

Cutting back on investing in our most underserved communities risks widening this tragic gap, undoing the significant but unfinished progress of late.

In a city that remains starkly divided between affluent and disadvantaged residents, about half of public school students are considered “at risk” of academic under-achievement, as noted in a recent DC Public Charter School Board analysis. Under current law, those at risk are defined as students who are homeless, are in foster care, qualify for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or who are enrolled at a lower high school grade level than their age would normally dictate.

The mayor has committed to a 4% increase in the Uniform Per-Student Funding Formula (UPSFF) that finances school operation costs for DC’s traditional and chartered public schools. In addition to keeping that pledge, the mayor should focus on increasing the at-risk funding weight from 0.2225 to 0.370, as recommended by a 2013 city-commissioned adequacy study and increasing the base UPSFF from $10,980 to $11,840 — in line with another city recommendation. No less important are fully funding the expansion of the Department of Behavioral Health’s school-based mental health program and indexing facilities funding for charters, which receive one-third as much per student when compared to DCPS.

As we slowly bring life in the District closer to what we knew before this crisis and adjust and adapt, the District’s most disadvantaged children — thousands of whom already suffer social and economic exclusion from society’s mainstream, and whose communities are paying a higher price for the pandemic — shouldn’t have to pay still more.

Alison Collier is interim co-executive director of Friends of Choice in Urban Schools (FOCUS).

About commentaries

The DC Line welcomes commentaries representing various viewpoints on local issues of concern, but the opinions expressed do not represent those of The DC Line. Submissions of up to 850 words may be sent to editor Chris Kain at chriskain@thedcline.org.

Comments are closed.