Prior to implementing a decade-old law with new powers to preserve affordable housing, DC government is still finalizing a list of qualified developers

While there is more rental housing in the District of Columbia today than a decade ago, the share of units available for less than $1,000 per month has shrunk from 69 percent to 34 percent. As the DC government works to preserve and grow the city’s affordable housing stock, officials have a new tool, as of late last year, to help reach those goals. The District Opportunity to Purchase Act, introduced by then-Ward 8 Council member Marion Barry, became law in 2008 — but nearly a decade passed before city officials put into place regulations enabling its use.

DOPA allows the city to purchase properties with five or more units if at least a quarter of the apartments are affordable for people making less than 50 percent of the area median income, a number set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development that is used to determine eligibility for housing assistance programs. The law does not apply to homeowners renting out single units such as basement apartments, or to small landlords with buildings of up to four units. DC housing officials are finalizing a list of qualified developers who can exercise the government’s purchase rights if and when the District opts to invoke the law — which enables the purchase of a residential building before it hits the private market if the tenants choose not to exercise their own rights to purchase it.

The city can also use DOPA to target “at-risk” affordable properties, including those with elderly and disabled tenants or a high number of family-sized units. The law’s criteria make it more likely that the city will opt to acquire a property if it is located in a neighborhood where average housing costs are above fair market rent, a number set by HUD to determine the value of housing vouchers. The average fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the DC metro area is currently $1,655.

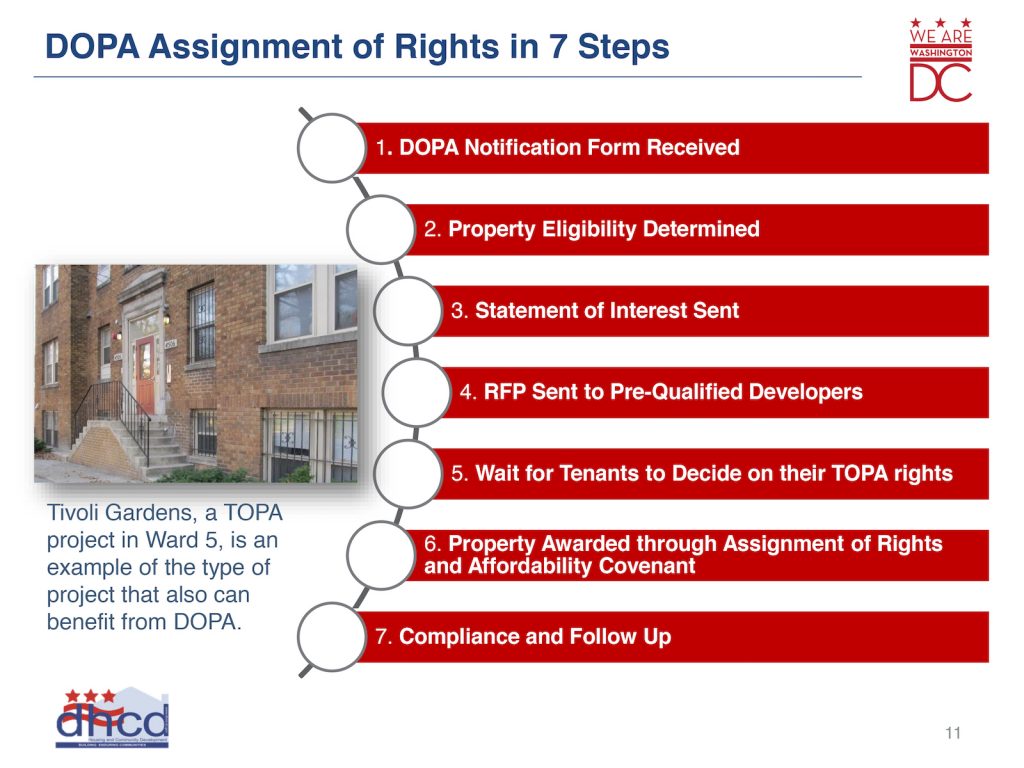

The city can use DOPA only after the tenants of a property have had a chance to exercise their right to purchase under the existing Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, which dates to the 1970s. While the two processes will run concurrently when a property is offered for sale, the city’s DOPA claims are always secondary to the tenants’ rights under TOPA.

Ana Van Balen, affordable housing preservation officer at the DC Department of Housing and Community Development, described DOPA as a unique tool that complements existing means of preservation, like TOPA. “This is an exciting time to be working on affordable housing in the District,” Van Balen said. “Other jurisdictions are looking to us in this effort.”

DHCD issued its first set of proposed regulations in December 2017, followed by revised rules last June with significant edits in response to public comments. The regulations defined what constitutes affordable housing and how the DOPA timeline would run concurrently with TOPA. The rules also outline the city’s ability to assign purchase rights to a private, qualified developer, letting developers purchase a property if the city decides it wants to preserve the property but not acquire it directly.

Only pre-qualified developers will be eligible to bid on DHCD projects when the department receives a DOPA notice and determines that the property qualifies for preservation. DHCD released an initial request for qualifications on Nov. 16, the same day it published the final DOPA regulations. Applications for pre-qualification were due Jan. 11 and the final list will be published on DHCD’s website once the review process is complete. Participating developers will be expected to maintain affordable rents after they purchase a property.

In February, at the request of the mayor, DC Council Chairman Phil Mendelson introduced legislation that would amend DOPA’s definition of affordable to be “equal to or less than 30% of the annual income of a household with an income of 60% of the area median income.” The present law specifies households with an income of 50 percent of the AMI, and the chief financial officer’s fiscal analysis notes that the “new affordability threshold could increase the number of housing accommodations eligible for purchase through DOPA.” That would not affect the availability of funding, however, since decisions on whether to invoke DOPA are discretionary.

Though the median annual income for a household of four was $117,200 in 2018, for Black families in the city it was $41,000, according to a report completed by the first appointed chair to the DC Commission on African American Affairs.

The amendment was referred to the Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization, where it awaits committee review.

Implementation of DOPA through adoption of the long-awaited regulations was one of six recommendations of the mayor’s Housing Preservation Strike Force in its 2016 report on how to preserve the city’s existing affordable housing stock. Creation of the Public-Private Affordable Housing Preservation Unit that Van Balen heads was another of the six recommendations.

Van Balen said DOPA is a unique tool that will work in conjunction with TOPA and the Housing Production Trust Fund to overcome obstacles to housing preservation in the District, such as ever-growing rental and construction costs. “In the next four years, we will have other good outcomes to look to,” Van Balen said. “We are excited to move forward and know DOPA will be a part of that.”

This article was co-published with Street Sense Media.

Comments are closed.